You may be too old for London's art scene.

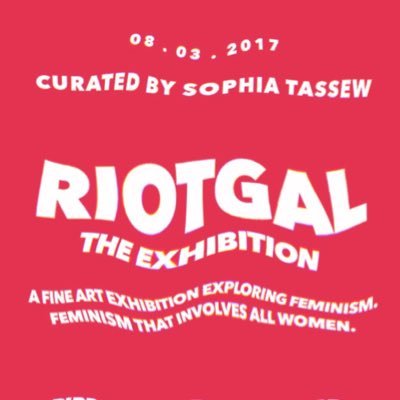

On a Wednesday night near Covent Garden, about a hundred teenagers and twentysomethings gathered in a pink-tinted gallery space at the Hospital Club for the opening of RIOTGAL. Executed by “Art Director. Exhibition curator. Uni drop out.” Sophia Tassew, RIOTGAL is an exhibition celebrating black women and women of color through the photography, drawing, painting, and film of five local women artists, including Tassew. Its name inspired by the 90s riot grrrl movement in the United States, RIOTGAL features works like Listen, a video montage of “iconic feminist moments throughout history,” that center black women, who are often excluded from mainstream - read, white - feminism.

Tassew is 20 years old, and her artists’ ages range from about 20 to 24. By the looks of them, the majority of the friends, siblings, and art kids who showed up for the opening weren’t any older. Still, the crowd, dressed in primary colored-jackets and retro wire-framed glasses, dreads piled high and baby hairs slicked down, circled the art and each other with an air both serious and unpretentious. You could tell from their gestures and the artists’ remarks that these young people already have a keen understanding of politics, both personal and global, as well as strong aesthetic sensibilities. As Tassew says (tweets), “Modern art shouldn't be exclusive to old white people in fancy galleries. That's [why] I'm curating exhibitions that we can relate to.” Hell yes. Here are our favorites from the show:

Lindo Khandela, Reclamation

South African-born Khandela weaves ndebele patterns and world maps into her big, saturated, portraits of black women both faceless and famous. Khandela’s paintings clap back at rape culture in candy tones, but they’re anything but sweet. In our favorite piece, a woman stands dressed in nothing but underwear, her hand clamped firmly between her legs. Her face unseen, the figure expresses sexuality and pleasure not packaged for any external actor, but rather owned exclusively by herself.

Erica Nuamah

The abstracted body parts are grotesque, pasty, and explicit, yet they make you look closer. You recognize these as familiar parts - mundane ones, even. A vulva here, a breast there. Though not idealized like the female bodies you’re used to seeing, you grow comfortable looking at these images and think about other things, like the artist’s color choices. And that is Erica Nuamah’s goal - to make you see yourself, and question your self-perception. Assuming a female viewer, Nuamah’s grid of body parts is a mirror of the worst ways we see ourselves, and a celebration of our true beauty.

Pippa Alice, Pippa’s Angels

Alice’s photo tributes to four female friends are all lovely, but the most striking is that of a black woman, sitting on a couch in bandeau and skirt, her posture balletic, her stomach soft and round, her gaze confident with a hint of mischief. Not sexualized, quotidian, and warm in that way that only film photography can produce, each of Alice’s portraits is laced with a familiar, female gaze. They capture the everyday moments of girl life, like those spent chilling on the couch in your underwear - the moments glamorous in their distinct lack of glamor.

Photo courtesy of Sophia Tassew